Criticism Is What We Engaged in When We Looked at the Elements and Principles of Art

Fine art criticism is the discussion or evaluation of visual fine art.[1] [2] [3] Art critics usually criticize art in the context of aesthetics or the theory of beauty.[2] [3] A goal of art criticism is the pursuit of a rational basis for art appreciation[ane] [2] [three] just it is questionable whether such criticism can transcend prevailing socio-political circumstances.[iv]

The diversity of creative movements has resulted in a partition of fine art criticism into unlike disciplines which may each use different criteria for their judgements.[iii] [5] The almost common division in the field of criticism is between historical criticism and evaluation, a grade of art history, and contemporary criticism of piece of work by living artists.[1] [2] [three]

Despite perceptions that fine art criticism is a much lower adventure activity than making art, opinions of electric current fine art are ever liable to desperate corrections with the passage of time.[2] Critics of the past are oft ridiculed for dismissing artists now venerated (like the early piece of work of the Impressionists).[3] [half-dozen] [7] Some art movements themselves were named disparagingly by critics, with the proper name later on adopted as a sort of badge of honour by the artists of the way (e.g., Impressionism, Cubism), with the original negative meaning forgotten.[six] [8] [nine]

Artists take often had an uneasy human relationship with their critics. Artists normally need positive opinions from critics for their work to exist viewed and purchased; unfortunately for the artists, just afterward generations may understand it.[two] [x]

Art is an of import office of being human and can be plant through all aspects of our lives, regardless of the culture or times. In that location are many different variables that decide ane's judgment of art such every bit aesthetics, cognition or perception. Art can be objective or subjective based on personal preference toward aesthetics and form. It can be based on the elements and principle of pattern and past social and cultural acceptance. Art is a basic human instinct with a diverse range of form and expression. Art can stand alone with an instantaneous judgment or can be viewed with a deeper more educated knowledge. Aesthetic, pragmatic, expressive, formalist, relativist, processional, imitation, ritual, cognition, mimetic and postmodern theories are some of many theories to criticize and appreciate art. Art criticism and appreciation tin can be subjective based on personal preference toward aesthetics and class, or information technology can be based on the elements and principle of pattern and past social and cultural credence.[ citation needed ]

Definition [edit]

Art criticism has many and oftentimes numerous subjective viewpoints which are about as varied as there are people practising it.[2] [3] It is hard to come by a more stable definition than the activity being related to the discussion and interpretation of art and its value.[iii] Depending on who is writing on the subject field, "art criticism" itself may be obviated as a directly goal or it may include fine art history inside its framework.[3] Regardless of definitional problems, art criticism can refer to the history of the craft in its essays and art history itself may apply critical methods implicitly.[two] [three] [7] Co-ordinate to art historian R. Siva Kumar, "The borders between art history and fine art criticism... are no more as firmly drawn equally they once used to be. It peradventure began with fine art historians taking interest in modern art."[xi]

Methodology [edit]

Fine art criticism includes a descriptive attribute,[3] where the work of art is sufficiently translated into words so equally to allow a example to exist made.[2] [3] [7] [12] The evaluation of a work of art that follows the description (or is interspersed with it) depends equally much on the creative person'southward output as on the experience of the critic.[2] [3] [9] In that location is in an action with such a marked subjective component a variety of ways in which it can be pursued.[2] [3] [7] As extremes in a possible spectrum,[thirteen] while some favour merely remarking on the immediate impressions caused past an artistic object,[2] [3] others prefer a more systematic approach calling on technical knowledge, favoured artful theory and the known sociocultural context the artist is immersed in to discern their intent.[ii] [3] [7]

History [edit]

Critiques of art likely originated with the origins of art itself, equally evidenced by texts found in the works of Plato, Vitruvius or Augustine of Hippo among others, that contain early on forms of fine art criticism.[three] Also, wealthy patrons have employed, at least since the start of Renaissance, intermediary fine art-evaluators to assist them in the procurement of commissions and/or finished pieces.[14] [15]

Origins [edit]

Art criticism as a genre of writing, obtained its modernistic course in the 18th century.[three] The primeval use of the term art criticism was past the English painter Jonathan Richardson in his 1719 publication An Essay on the Whole Fine art of Criticism. In this piece of work, he attempted to create an objective organization for the ranking of works of fine art. Seven categories, including drawing, composition, invention and colouring, were given a score from 0 to 18, which were combined to give a final score. The term he introduced quickly defenseless on, especially every bit the English centre grade began to exist more discerning in their art acquisitions, as symbols of their flaunted social status.[16]

In France and England in the mid 1700s, public involvement in art began to become widespread, and art was regularly exhibited at the Salons in Paris and the Summer Exhibitions of London. The first writers to acquire an private reputation equally art critics in 18th-century France were Jean-Baptiste Dubos with his Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et sur la peinture (1718)[17] which garnered the acclamation of Voltaire for the sagacity of his arroyo to artful theory;[18] and Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne with Reflexions sur quelques causes de l'état présent de la peinture en France who wrote nigh the Salon of 1746,[19] commenting on the socioeconomic framework of the production of the then popular Bizarre fine art style,[20] which led to a perception of anti-monarchist sentiments in the text.[21]

The 18th-century French author Denis Diderot greatly advanced the medium of art criticism. Diderot's "The Salon of 1765"[22] was one of the first real attempts to capture fine art in words.[23] Co-ordinate to fine art historian Thomas E. Crow, "When Diderot took up art criticism it was on the heels of the first generation of professional writers who made information technology their business organisation to offer descriptions and judgments of contemporary painting and sculpture. The need for such commentary was a production of the similarly novel institution of regular, costless, public exhibitions of the latest art".[24]

Meanwhile, in England an exhibition of the Society of Arts in 1762 and later, in 1766, prompted a flurry of disquisitional, though anonymous, pamphlets. Newspapers and periodicals of the period, such equally the London Chronicle, began to conduct columns for art criticism; a form that took off with the foundation of the Royal Academy in 1768. In the 1770s, the Morning Chronicle became the starting time newspaper to systematically review the art featured at exhibitions.[sixteen]

19th century [edit]

John Ruskin, the preeminent art critic of 19th century England.

From the 19th century onwards, fine art criticism became a more common vocation and fifty-fifty a profession,[3] developing at times formalised methods based on detail artful theories.[2] [3] [five] [xiii] In French republic, a rift emerged in the 1820s between the proponents of traditional neo-classical forms of art and the new romantic style. The Neoclassicists, under Étienne-Jean Delécluze defended the classical platonic and preferred carefully finished course in paintings. Romantics, such every bit Stendhal, criticized the onetime styles every bit overly formulaic and devoid of any feeling. Instead, they championed the new expressive, Idealistic, and emotional nuances of Romantic art. A similar, though more than muted, contend too occurred in England.[xvi]

One of the prominent critics in England at the time was William Hazlitt, a painter and essayist. He wrote virtually his deep pleasure in art and his belief that the arts could exist used to improve mankind's generosity of spirit and knowledge of the globe effectually it. He was one of a ascent tide of English critics that began to grow uneasy with the increasingly abstract management J. K. W. Turner'due south landscape fine art was moving in.[16]

One of the bully critics of the 19th century was John Ruskin. In 1843 he published Modern Painters, which repeated concepts from "Mural and Portrait-Painting" in The Yankee (1829) by first American art critic John Neal[25] in its distinction between "things seen by the artist" and "things as they are."[26] Through painstaking analysis and attention to item, Ruskin achieved what art historian E. H. Gombrich called "the most ambitious work of scientific fine art criticism ever attempted." Ruskin became renowned for his rich and flowing prose, and afterwards in life he branched out to become an agile and wide-ranging critic, publishing works on architecture and Renaissance art, including the Stones of Venice.

Another dominating figure in 19th-century art criticism, was the French poet Charles Baudelaire, whose first published piece of work was his art review Salon of 1845,[27] which attracted immediate attending for its boldness.[28] Many of his disquisitional opinions were novel in their fourth dimension,[28] including his championing of Eugène Delacroix.[29] When Édouard Manet's famous Olympia (1865), a portrait of a nude courtesan, provoked a scandal for its blatant realism,[30] Baudelaire worked privately to support his friend.[31] He claimed that "criticism should be partial, impassioned, political— that is to say, formed from an exclusive point of view, but also from a point of view that opens up the greatest number of horizons". He tried to move the argue from the onetime binary positions of previous decades, declaring that "the true painter, will be he who tin can wring from contemporary life its epic aspect and make us come across and understand, with colour or in drawing, how great and poetic we are in our cravats and our polished boots".[sixteen]

In 1877, John Ruskin derided Nocturne in Blackness and Gold: The Falling Rocket after the creative person, James McNeill Whistler, showed it at Grosvenor Gallery:[32] "I accept seen, and heard, much of Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb inquire two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public'due south face up."[33] This criticism provoked Whistler into suing the critic for libel.[34] [35] The ensuing court case proved to be a Pyrrhic victory for Whistler.[36] [37] [38]

Turn of the twentieth century [edit]

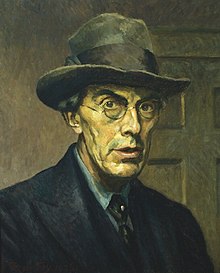

Cocky portrait of Roger Fry, described by the art historian Kenneth Clark as "incomparably the greatest influence on taste since Ruskin... In so far every bit taste tin can be changed past one man, it was inverse by Roger Fry".[39]

Towards the finish of the 19th century a move towards abstraction, as opposed to specific content, began to proceeds ground in England, notably championed by the playwright Oscar Wilde. Past the early twentieth century these attitudes formally coalesced into a coherent philosophy, through the work of Bloomsbury Grouping members Roger Fry and Clive Bell.[twoscore] [41] As an art historian in the 1890s, Fry became intrigued with the new modernist fine art and its shift away from traditional depiction. His 1910 exhibition of what he called post-Impressionist fine art attracted much criticism for its iconoclasm. He vigorously defended himself in a lecture, in which he argued that art had moved to try to detect the language of pure imagination, rather than the staid and, to his heed, dishonest scientific capturing of landscape.[42] [43] Fry's argument proved to be very influential at the time, particularly amongst the progressive elite. Virginia Woolf remarked that: "in or about December 1910 [the engagement Fry gave his lecture] human character changed."[16]

Independently, and at the same fourth dimension, Clive Bell argued in his 1914 book Fine art that all art work has its detail 'significant form', while the conventional subject affair was substantially irrelevant. This work laid the foundations for the formalist approach to art.[5] In 1920, Fry argued that "it's nonetheless to me if I represent a Christ or a saucepan since it's the form, and non the object itself, that interests me." Equally well as beingness a proponent of formalism, he argued that the value of art lies in its ability to produce a distinctive aesthetic experience in the viewer. an experience he called "aesthetic emotion". He defined it as that experience which is angry by pregnant form. He also suggested that the reason we experience aesthetic emotion in response to the significant form of a work of art was that nosotros perceive that form as an expression of an experience the artist has. The artist's feel in turn, he suggested, was the experience of seeing ordinary objects in the world as pure form: the experience 1 has when one sees something not as a means to something else, but equally an finish in itself.[44]

Herbert Read was a champion of modern British artists such equally Paul Nash, Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth and became associated with Nash'due south contemporary arts group Unit Ane. He focused on the modernism of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and published an influential 1929 essay on the meaning of art in The Listener.[45] [46] [47] [48] He also edited the trend-setting Burlington Mag (1933–38) and helped organise the London International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936.[49]

Since 1945 [edit]

As in the example of Baudelaire in the 19th century, the poet-as-critic phenomenon appeared once more in the 20th, when French poet Apollinaire became the champion of Cubism.[fifty] [51] Later, French writer and hero of the Resistance André Malraux wrote extensively on art,[52] going well across the limits of his native Europe.[53] His confidence that the vanguard in Latin America lay in Mexican Muralism (Orozco, Rivera and Siqueiros)[ citation needed ] changed after his trip to Buenos Aires in 1958. After visiting the studios of several Argentine artists in the visitor of the young Director of the Museum of Modernistic Art of Buenos Aires Rafael Squirru, Malraux alleged the new vanguard to lie in Argentina'southward new artistic movements.[ commendation needed ] Squirru, a poet-critic who became Cultural Director of the OAS in Washington, D.C., during the 1960s, was the last to interview Edward Hopper before his death, contributing to a revival of interest in the American artist.[54]

In the 1940s there were non only few galleries (The Art of This Century) but too few critics who were willing to follow the work of the New York Vanguard.[55] In that location were also a few artists with a literary background, among them Robert Motherwell and Barnett Newman who functioned as critics as well.[56] [57] [58]

Although New York and the world were unfamiliar with the New York advanced,[55] by the tardily 1940s most of the artists who accept become household names today had their well established patron critics.[59] Clement Greenberg advocated Jackson Pollock and the color field painters similar Clyfford Withal, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, Adolph Gottlieb and Hans Hofmann.[60] [61] [62] [63] [64] [65] [66] Harold Rosenberg seemed to prefer the action painters such every bit Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline.[67] [68] Thomas B. Hess, the managing editor of ARTnews, championed Willem de Kooning.[69]

The new critics elevated their protégés by casting other artists as "followers" or ignoring those who did not serve their promotional goal.[5] [70] As an example, in 1958, Mark Tobey "became the first American painter since Whistler (1895) to win acme prize at the Biennale of Venice. New York's ii leading art magazines were not interested. Arts mentioned the historic result only in a news column and Fine art News (Managing editor: Thomas B. Hess) ignored information technology completely. The New York Times and Life printed feature articles".[71]

Barnett Newman, a late member of the Uptown Group wrote catalogue forewords and reviews and by the belatedly 1940s became an exhibiting artist at Betty Parsons Gallery. His commencement solo show was in 1948. Presently after his showtime exhibition, Barnett Newman remarked in ane of the Artists' Session at Studio 35: "We are in the procedure of making the world, to a certain extent, in our own image".[72] Utilizing his writing skills, Newman fought every step of the fashion to reinforce his newly established prototype as an artist and to promote his work. An instance is his letter to Sidney Janis on 9 April 1955:

It is true that Rothko talks the fighter. He fights, however, to submit to the philistine world. My struggle confronting bourgeois club has involved the total rejection of information technology.[73]

The person thought to have had most to do with the promotion of this style was a New York Trotskyist, Clement Greenberg.[5] [59] As long fourth dimension fine art critic for the Partisan Review and The Nation, he became an early and literate proponent of Abstract Expressionism.[5] Artist Robert Motherwell, well-heeled, joined Greenberg in promoting a manner that fit the political climate and the intellectual rebelliousness of the era.[74]

Clement Greenberg proclaimed Abstruse Expressionism and Jackson Pollock in particular as the epitome of aesthetic value. Greenberg supported Pollock's piece of work on formalistic grounds as merely the best painting of its mean solar day and the culmination of an art tradition going back via Cubism and Cézanne to Monet, in which painting became always "purer" and more concentrated in what was "essential" to it, the making of marks on a flat surface.[75]

Jackson Pollock'due south piece of work has always polarised critics. Harold Rosenberg spoke of the transformation of painting into an existential drama in Pollock's work, in which "what was to get on the sail was non a picture just an upshot". "The big moment came when it was decided to paint 'just to paint'. The gesture on the canvas was a gesture of liberation from value—political, aesthetic, moral."[76]

Ane of the most vocal critics of Abstract Expressionism at the time was New York Times art critic John Canaday.[77] Meyer Schapiro and Leo Steinberg were also important postwar fine art historians who voiced support for Abstract Expressionism.[78] [79] During the early to mid sixties younger art critics Michael Fried, Rosalind Krauss and Robert Hughes added considerable insights into the critical dialectic that continues to grow effectually Abstract Expressionism.[eighty] [81] [82]

Feminist art criticism [edit]

Feminist fine art criticism emerged in the 1970s from the wider feminist movement every bit the critical exam of both visual representations of women in fine art and art produced by women.[83] It continues to be a major field of art criticism.

Today [edit]

Art critics today work not only in print media and in specialist fine art magazines likewise as newspapers. Art critics appear besides on the internet, TV, and radio, as well as in museums and galleries.[1] [84] Many are likewise employed in universities or as fine art educators for museums. Art critics curate exhibitions and are often employed to write exhibition catalogues.[1] [ii] Art critics have their own organisation, a UNESCO not-governmental organisation, called the International Association of Art Critics which has around 76 national sections and a political not-aligned section for refugees and exiles.[85]

Art blogs [edit]

Since the early 21st century, online fine art critical websites and art blogs have cropped up around the world to add their voices to the art earth.[86] [87] Many of these writers use social media resources like Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr and Google+ to innovate readers to their opinions about fine art criticism.

See also [edit]

- Art history

- Art critic

- Documenta 12 magazines (contemporary examples of art criticism)

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e "Art Criticism". Comprehensive Art Pedagogy. North Texas Institute For Educators on the Visual Arts. Retrieved 12 Dec 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j m l chiliad due north o Gemtou, Eleni (2010). "Subjectivity in Art History and Art Criticism" (PDF). Rupkatha Periodical on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities. 2 (1): ii–thirteen. doi:10.21659/rupkatha.v2n1.02 . Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f thou h i j chiliad 50 m due north o p q r due south t Elkins, James (1996). "Art Criticism". In Jane Turner (ed.). Grove Dictionary of Art. Oxford Academy Press.

- ^ Kaplan, Marty. "The curious case of criticism." Jewish Journal. 23 Jan 2014.

- ^ a b c d eastward f Tekiner, Deniz (2006). "Formalist Art Criticism and the Politics of Significant". Social Justice. 33 (2 (104) – Art, Ability, and Social Modify): 31–44. JSTOR 29768369.

- ^ a b Rewald, John (1973). The History of Impressionism (4th, Revised Ed.). New York: The Museum of Modern Fine art. p. 323 ISBN 0-87070-360-9

- ^ a b c d e Ackerman, James S. (Winter 1960). "Art History and the Problems of Criticism". Daedalus. 89 (1 – The Visual Arts Today): 253–263. JSTOR 20026565.

- ^ Christopher Green, 2009, Cubism, MoMA, Grove Art Online, Oxford University Press

- ^ a b Fishman, Solomon (1963). The Interpretation of Art: Essays on the Art Criticism of John Ruskin, Walter Pater, Clive Bell, Robert Fry, and Herbert Read. University of California Printing. p. six.

- ^ Seenan, Gerard (20 Apr 2004). "Painting past ridiculed but popular artist sells for £744,800". The Guardian . Retrieved 12 Dec 2013.

- ^ "Humanities underground » All the Shared Experiences of the Lived World".

- ^ Fishman, Solomon (1963). The Interpretation of Art: Essays on the Fine art Criticism of John Ruskin, Walter Pater, Clive Bong, Robert Fry, and Herbert Read. Academy of California Press. p. 3.

- ^ a b Fishman, Solomon (1963). The Interpretation of Fine art: Essays on the Art Criticism of John Ruskin, Walter Pater, Clive Bong, Robert Fry, and Herbert Read. University of California Press. p. 5.

- ^ Gilbert, Creighton E. (Summertime 1998). "What Did the Renaissance Patron Buy?" (PDF). Renaissance Quarterly. The University of Chicago Printing on behalf of the Renaissance Social club of America. 51 (2): 392–450. doi:10.2307/2901572. JSTOR 2901572. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ Nagel, Alexander (2003). "Art equally Gift: Liberal Fine art and Religious Reform in the Renaissance" (PDF). Negotiating the Souvenir: Pre-Mod Figurations of Commutation. pp. 319–360. Retrieved fourteen December 2013.

- ^ a b c d eastward f "A History of Art Criticism" (PDF) . Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Dubos, Jean-Baptiste (1732). Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et sur la peinture (in French) (3rd ed.). Utrecht: E. Neaulme.

- ^ Voltaire (1874). Charles Louandre (ed.). Le Siècle de Louis XIV (in French). Paris: Charpentier et Cie, Libraires-Éditeurs. p. 581. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ La Font de Saint-Yenne, Étienne (1747). Reflexions sur quelques causes de l'état présent de la peinture en France : avec un examen des principaux ouvrages exposés au Louvre le mois d'août 1746 (in French). The Hague: Jean Neaulme.

- ^ Saisselin, Rémy G. (1992). The Enlightenment Against the Bizarre: Economics and Aesthetics in the Eighteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 49–50. Retrieved x December 2013.

- ^ Walter, Nancy Paige Ryan (1995). From Armida to Cornelia: Women and Representation in Prerevolutionary France (MA). Texas Tech Academy. p. xi. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Diderot, Denis (1795). François Buisson (ed.). Essais sur la peinture (in French). Paris: François Buisson. pp. 118–407. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Morley, John (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 205.

- ^ Crow, Thomas E. (1995). "Introduction". In Denis Diderot (ed.). Diderot on Art, Book I: The Salon of 1765 and Notes on Painting. Yale University Printing. p. x.

- ^ Dickson, Harold Edward (1943). Observations on American Art: Selections from the Writings of John Neal (1793-1876). State College, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State College. p. 9. OCLC 775870.

- ^ Orestano, Francesca (2012). "Chapter 6: John Neal, the Rise of the Critick, and the Rise of American Art". In Watts, Edward; Carlson, David J. (eds.). John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN978-ane-61148-420-five.

- ^ Baudelaire, Charles (1868). "Salon de 1845". Curiosités esthétiques: Salon 1845–1859. M. Lévy. pp. 5–76. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. three (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 537.

- ^ Richardson, Joanna (1994). Baudelaire. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 110. ISBN0-312-11476-1. OCLC 30736784.

- ^ "Édouard Manet's Olympia by Beth Harris and Steven Zucker". Smarthistory. Khan Academy. Retrieved 11 Feb 2013.

- ^ Hyslop, Lois Boe (1980). Baudelaire, Man of His Fourth dimension. Yale University Printing. p. 51. ISBN0-300-02513-0.

- ^ Merrill, Linda, Later Whistler: The Artist and His Influence on American Painting. City: Publisher, 2003. p. 112

- ^ Ronald Anderson and Anne Koval, James McNeill Whistler: Beyond the Myth, Carroll & Graf, New York, 1994, p. 215

- ^ Stuttaford, Genevieve. "Nonfiction – the Aesthetic Movement by Lionel Lambourne." Vol. 243. (1996).

- ^ Ronald Anderson and Anne Koval, James McNeill Whistler: Across the Myth, Carroll & Graf, New York, 1994, p. 216

- ^ Whistler, James Abbott McNeill. WebMuseumn, Paris

- ^ Prideaux, Tom. The Globe of Whistler. New York: Time-Life Books, 1970. p. 123

- ^ Peters, Lisa North. (1998). James McNeil Whistler. New Line Books. pp. 51–52 ISBN 1-880908-70-0.

- ^ IAN CHILVERS. "Fry, Roger." The Curtailed Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. 2003. Encyclopedia.com. nine March 2009 <http://world wide web.encyclopedia.com>.Retrieved [ permanent dead link ] ix March 2009

- ^ "Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury Biographies: Roger Fry, as art critic | Tate". Archive Journeys. Tate. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury Group Profiles | Tate". Archive Journeys. Tate. Retrieved ten December 2013.

- ^ "Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury Biographies: Roger Fry, ideas | Tate". Archive Journeys. Tate. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "Archive Journeys: Bloomsbury Biographies: Roger Fry, modern art | Tate". Archive Journeys. Tate. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Clive Bell (2010). Art. General Books LLC. ISBN9781770451858.

- ^ Overton, Tom (2009). "Paul Nash (1889–1946)". Venice Biennale. British Council. Archived from the original on 15 Dec 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Overton, Tom (2009). "Ben Nicholson (1894–1982)". Venice Biennale. British Council. Archived from the original on fifteen December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Overton, Tom (2009). "Henry Moore (1898–1986)". Venice Biennale. British Quango. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved xi December 2013.

- ^ Overton, Tom (2009). "Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975)". Venice Biennale. British Council. Archived from the original on fifteen Dec 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "A History of Art Criticism" (PDF) . Retrieved 17 Dec 2012.

- ^ Conley, Katharine (Leap 2005). "The Cubist Painters by Guillaume Apollinaire; Peter Read". French Forum. 30 (2): 139–141. doi:10.1353/frf.2005.0030. JSTOR 40552391. S2CID 191632519.

- ^ Mathews, Timothy (Summer 1988). "Apollinaire and Cubism?" (PDF). Way. 22 (2): 275–298. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Allan, Derek (2009). Art and the Man Adventure, André Malraux's Theory of Art. Rodopi.

- ^ Hudek, Antony (2012). "The Vocal Plow". Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies. x (1): 64–65. doi:ten.5334/jcms.1011210.

- ^ Levin, Gail (1998). Edward Hopper : an intimate biography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ a b Wolf, Justin. "The Art Story: Gallery – The Art of This Century Gallery". The Art Story. The Art Story Foundation. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Archives of American Art. "Oral history interview with Robert Motherwell, 1971 Nov. 24-1974 May one – Oral Histories | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". Aaa.si.edu. Retrieved vii December 2011.

- ^ "Robert Motherwell". Tate. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ The Barnett Newman Foundation website: Chronology of the Creative person's Life page

- ^ a b "Painters in Postwar New York Metropolis". Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 12 Dec 2013.

- ^ Wolf, Justin. "Abstract Expressionism". The Art Story. The Art Story Foundation. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Jackson Pollock, Mural (1943) University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa Urban center.

- ^ Greenberg, Clement (1955). "American-Type Painting". Partisan Review: 58.

- ^ "American Abstruse Expressionism: Painting Action and Colorfields". Colour Vision & Art. webexhibits.org. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ "Chronology". The Barnett Newman Foundation. Retrieved 12 Dec 2013.

- ^ "Special Exhibitions – Adolph Gottlieb". The Jewish Museum. Archived from the original on xiii August 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ "Hans Hofmann: Biography". The Estate of Hans Hofmann. Archived from the original on 29 Jan 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Stevens, Marker; Annalyn Swan (8 November 2004). "When de Kooning Was Rex". New York.

- ^ Wolf, Justin. "Harold Rosenberg". The Art Story. The Art Story Foundation. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Wolf, Justin. "Thomas B. Hess". The Art Story. The Art Story Foundation. Retrieved 12 Dec 2013.

- ^ Thomas B. Hess, "Willem de Kooning", George Braziller, Inc. New York, 1959 p.:13

- ^ Marker Tobey. Arno Press. 1980. ISBN9780405128936.

- ^ Barnett Newman Selected Writings and Interviews, (ed.) by John P. O'Neill, pgs.: 240–241, University of California Press, 1990

- ^ Barnett Newman Selected Writings Interviews, (ed.) by John P. O'Neill, p.: 201, University of California Press, 1990.

- ^ Glueck, Grace (18 July 1991). "Robert Motherwell, Master of Abstract, Dies". The New York Times . Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Clement Greenberg, Fine art and Culture Disquisitional essays, ("The Crunch of the Easel Moving-picture show"), Beacon Press, 1961 pp.:154–157

- ^ Harold Rosenberg, The Tradition of the New, Affiliate 2, "The American Action Painter", Da Capo Press, 1959 pp.:23–39

- ^ Wolf, Justin. "John Canaday". The Fine art Story. The Fine art Story Foundation. Retrieved 12 Dec 2013.

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (14 August 1994). "A Critic Turns ninety; Meyer Schapiro". The New York Times . Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ McGuire, Kristi (15 March 2011). "Remembering Leo Steinberg (1920–2011)". The Chicago Blog. Academy of Chicago Press. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Wolf, Justin. "Michael Fried". The Art Story. The Fine art Story Foundation. Retrieved 12 Dec 2013.

- ^ Wolf, Justin. "Rosalind Krauss". The Fine art Story. The Fine art Story Foundation. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Wolf, Justin. "Robert Hughes". The Art Story. The Art Story Foundation. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Deepwell, Katie (September 2012). "12 Step Guide to Feminist Fine art, Art History and Criticism" (PDF). N.paradoxa. online (21): 8.

- ^ Gratza, Agnieszka (17 October 2013). "Frieze or faculty? One art critic'due south move from academia to journalism". Guardian Professional person. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ "International Association of Art Critics". UNESCO NGO – db. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Greenish, Tyler. "Tyler Green". In Their Ain Words. New York Foundation for the Arts. Archived from the original on 25 November 2005. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Kaiser, Michael (14 November 2011). "The Decease of Criticism or Everyone Is a Critic". HuffPost . Retrieved 12 Dec 2013.

External links [edit]

- "AICA – International Association of Art Critics". Archived from the original on 22 September 2017.

- "Our critics' advice". Arts. Guardian News and Media Limited. eight July 2008.

- In this commodity Adrian Searle, among others, gives advice to ambitious, young, would-exist fine art critics.

- "Judgment and Gimmicky Art Criticism". Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. – conference, reading room, and bibliography

- Singerman, Howard. "The Myth of Criticism in the 1980s". X-TRA : Contemporary Fine art Quarterly. Archived from the original on one August 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_criticism

0 Response to "Criticism Is What We Engaged in When We Looked at the Elements and Principles of Art"

Post a Comment